Me on degree day. Was my beard ever that colour?! |

I realised this week that I've been working 30 years. Can you

imagine it? I hardly seem to have got my act together since leaving

the Royal College of Art in July 1975.

I was the first student - the only student, to start

with - in the natural history illustration department,

set up by John Norris Wood in 1972, and, during

my three years, I worked, on and off, on this large painting of

birds in the college greenhouse (below), which formed the

centrepiece of my degree show.

Once John was asking a couple of students if they'd

seen me about. They looked blank; 'He's the one who looks like Rasputin,'

said John. They realised who he meant immediately (I'd better explain

that I wore the fur-lined hooded cloak only on degree day). |

John Norris Wood in his natural habitat, the greenhouse, 1974 |

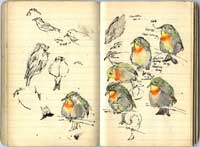

Student sketchbook:

Pekin Robin, London Zoo

|

Greenhouse Mural, 8ft x 4ft acrylic on chipboard, collection of

the Royal College of Art

|

Work in Progress

The

painting absorbed so much work. I'd ask John what he thought of

my progress since the previous week and he'd look around the painting,

trying to spot the area I'd been working on; I'd plug away at

it a leaf, or a bird, at a time. Each life-sized bird is labelled

with its common and Latin name. The

painting absorbed so much work. I'd ask John what he thought of

my progress since the previous week and he'd look around the painting,

trying to spot the area I'd been working on; I'd plug away at

it a leaf, or a bird, at a time. Each life-sized bird is labelled

with its common and Latin name.

There's a Tolkien story which I kept thinking of as I worked called

Leaf by Niggle, about a painter who could paint a leaf

better than he could paint a tree. I tried to give each leaf individual

attention and aimed to give the whole scene a theatrical Victorian

effect.

The greenhouse was on the top floor of the Kensington Gore building

so the roof of the Royal Albert Hall appears in the background (right).

Art historian Conal Shields thought the Java doves

were the most pre-Raphaelite corner of my painting. He described

the mural was an entire painting course in itself. I fought battles

over each section of it and learnt so much in the process.

After the first year, one of John's former tutors Edward

Bawden (1903 - 1989), took a look at the painting

and declared that it was finished already but it went on and on,

absorbing seemingly limitless amounts of work. Even when I'd got

it screwed to the wall in my degree show I found that I wanted to

add one last detail: a frog.

Liz Butterworth, who had been in the school of

fine art, the year above me, said that the geranium (below,

left) was the best bit of painting in the mural. It was the

first thing I'd done, three years earlier. |

|

|

Coming down to Earth

My long-suffering dad, Douglas

|

My mum and dad came to the degree ceremony; I'd won prizes and

been approached about various commissions and book projects and

there were bits of teaching in the offing but my dad wasn't terribly

impressed:

'I don't know how you're going to make a living,' he said when

we got back to Yorkshire, ' and I don't know if you know

how you're going to make a living, but I'm bloody well

not going to support you - on Monday you'll get down to the Labour

Exchange in Wakefield and sign on.'

When I think back to my degree day I still remember that feeling

of inadequacy, and it's difficult to shake it off, even today. Unless

you're an industrial designer with sponsorship or a golden boy like

the young David Hockney, who graduated a decade before me, it's

unlikely that you will have worked out how to make a living by the

time you leave college: you've been so immersed in your work that

it's hardly occurred to you. I might have had great ideas but they

were all still in the pipeline.

It was a wrench to leave the enthusiasm and the 'change the world'

idealism of South Kensington behind me and return to the crushing

constraints of hometown life. Without a phone - without e-mail in

those days - my college friends seemed a long way away, part of

a bright interval in my life.

I feel that if my dad was still with us and he could see how I'm

doing now, 30 years after leaving college, he'd still want me to

go out and get a proper job! |

My friend Gina in California e-mailed me

today; she says she read this quote and thought of me (and of herself):

'If you want to identify me ask me not where I live,

or what I like to eat, or how I comb my hair, but ask me what I am living

for, in detail, and ask me what I think is keeping me from living fully

for the things I want to live for. Between those two answers you can

determine the identity of any person.'

Thomas Merton, from The Man in the

Sycamore Tree

Richard Bell, richard@willowisland.co.uk |